- determine who to designate for the service management, cyber security and CIO functions

- assign these responsibilities at the level they deem appropriate, including assigning responsibility for more than one functional area to a single official

- establish other related senior roles, such as chief data officer, if appropriate for their organization

- their own functional areas, and functional authority for the IM/IT employees within the department

- for ensuring that departments have a coordinated response to various policy requirements

- collaborating effectively with other departmental officials and functional communities (such as privacy protection) across the department to improve the department’s services and operations (integrated governance is one way to support these linkages and collaboration between functional areas (see subsection 1.1 of this Guideline)

- reporting directly to the deputy head

- having regular bilateral or multilateral meetings with the deputy head

- being a member of the executive committee or other governance committee chaired by the deputy head

- communicating directly with the deputy head as needed

Considerations for designating an official responsible for leading a department’s service management function

The role for the official responsible for leading a department’s service management function could include the following:

- promoting a centralized perspective on service, allowing for improved efficiencies in the department’s policy and program areas

- providing leadership on managing service, including coordinating department-wide activities related to service, including:

- governance

- planning and performance measurement activities

- service inventory

- service standards

- service review

- client feedback

- administrative policy requirements and other TBS direction

- activities that stem from the service functional community

- other functions (IT, information, data, cyber security, privacy protection) are leveraged

- linkages are made to ensure a holistic approach to improving how service design and delivery are managed throughout the department

A deputy head is advised to not designate someone as both the Chief Financial Officer and the official responsible for leading the department’s service management function, as Subsection 4.1.10 of the Policy on Financial Management stipulates that Chief Financial Officers cannot be assigned non-financial corporate responsibilities that could compromise their objectivity.

In designating an official responsible for a department’s service management function, deputy heads can consider the following competencies:

- leadership competencies

- knowledge of departmental and government-wide governance frameworks (knowing the key partners and knowing where to go and when to go)

- knowledge of departmental and government-wide services

- familiarity with the service direction of the Government of Canada (that is, its priorities and strategies)

- familiarity with Treasury Board administrative policy requirements related to service (the Policy on Service and Digital and related policy instruments)

- knowledge of government obligations regarding IT, information, data, security, cyber security and privacy and how these relate to service

- knowledge of the department’s clients and their needs and expectations

- the ability, to collaborate and communicate

- knowledge of strategic planning and performance measurement

Considerations for designating a CIO responsible for leading a department’s IT, information and data management functions

Departmental CIOs are responsible for managing information and IT, and they are to be involved throughout the life cycle of how services are designed and delivered in order to continually improve how client’s needs are met. To fulfill the requirements set out in the Directive on Service and Digital, the CIO is responsible for:

- managing departmental information, data and IT

- being a strategic voice at the executive table who advises on digitally enabled approaches to meet departmental and government objectives and business needs

- ensuring that the department’s management practices for service, information, data and IT:

- align with the direction set by the Office of the Chief Information Officer of TBS

- follow legislative and policy requirements for protecting privacy

In addition to “consulting with the CIO of Canada before appointing, deploying, or otherwise replacing the departmental CIO” (subsection 4.5.2.3 of the Policy on Service and Digital), deputy heads may consider the following when designating a departmental CIO:

- leadership competencies

- knowledge of enterprise information and IT solutions and transformation in a dynamic and complex environment

- knowledge of service, IT, information and data technology functions

- knowledge of domestic or international partnerships to achieve departmental and government-wide outcomes

- understanding of IT, information, privacy protection and data governance

- understanding of work, workplace and workforce issues, trends, solutions and practices

- understanding of emerging government-wide direction on digital services and their impact on the department

- understanding of how the management of technology, information and data can help support and enable departmental and government-wide services

In discussions related to the appointment, deployment or replacement of a departmental CIO, deputy heads must ensure that “for the purposes of the Treasury Board Executive Group (EX) Qualifications Standard, the departmental CIO possesses an acceptable combination of education, training and experience” (subsection 4.5.2.4 of the Policy on Service and Digital). This requirement is mirrored at the government-wide level where the CIO of Canada is responsible for “providing enterprise-wide leadership on knowledge standards for the information and IT community, including determining the acceptable combination of education, training and experience required for the Treasury Board Executive Group (EX) Qualification Standard” (subsection 4.5.1.2 of the Policy on Service and Digital).

It is expected that CIO responsibilities in respect of information and data management would be carried out in close collaboration with other departmental officials, as necessary.

Deputy heads may also designate a Chief Data Officer (CDO) to support data governance and departmental capacity. CDOs can help leverage data to support the department’s objectives, in alignment with enterprise-wide priorities and CIO direction. CDOs can fall within the departmental CIO reporting structures or be separate and distinct. Where they are distinct, the CIO and CDO are expected to work collaboratively, to support and to realize data and information policy requirements.

Considerations for designating an official responsible for leading the departmental cyber security management function

The Designated Official for Cyber Security (DOCS) is responsible for providing department-wide strategic leadership, coordination and oversight on cyber security, in collaboration with the departmental CIO and Chief Security Officer (CSO), as appropriate. The DOCS is responsible for:

- ensuring that cyber security requirements and appropriate measures are applied in a risk-based, life-cycle approach to protect IT services, in line with the Directive on Security Management, Appendix B: Mandatory Procedures for information Technology Security Control

- identifying and establishing roles and responsibilities for reporting cyber security events and incidents in accordance with section 5 of the Government of Canada Cyber Security Event Management Plan and subsection 4.1.6 of the Directive on Security Management, and undertaking immediate action if there is a privacy breach and implementing associated mitigation measures

It is recommended that deputy heads consider the following when designating a DOCS:

- knowledge and awareness of domestic and international cyber security related trends, risks and their impacts

- knowledge of Government of Canada and departmental policy instruments relating to cyber security, the department’s business context and threat environment, and the department’s overall cyber security posture

- ability to enable strategic discussions regarding cyber security–risks, and to support integrated and informed risk management decisions at a senior official level

Taken together, these considerations are important because they provide deputy heads with an integrated view of government cyber security practices, risks and concerns.

The responsibilities of the DOCS are the same, regardless of the size of the department or agency Capacity should be considered when designating the DOCS to ensure that the designated individual can effectively fulfill their responsibilities. For example, the deputy head could designate the CSO as the DOCS. However, in larger departments and agencies, it may be preferred to have another senior official designated as the DOCS. In that case, specific responsibilities of the DOCS and the CSO in relation to cyber security would be defined in the integrated departmental governance structure.

1.2 Integrated governance

1.2.1 Description and associated requirements

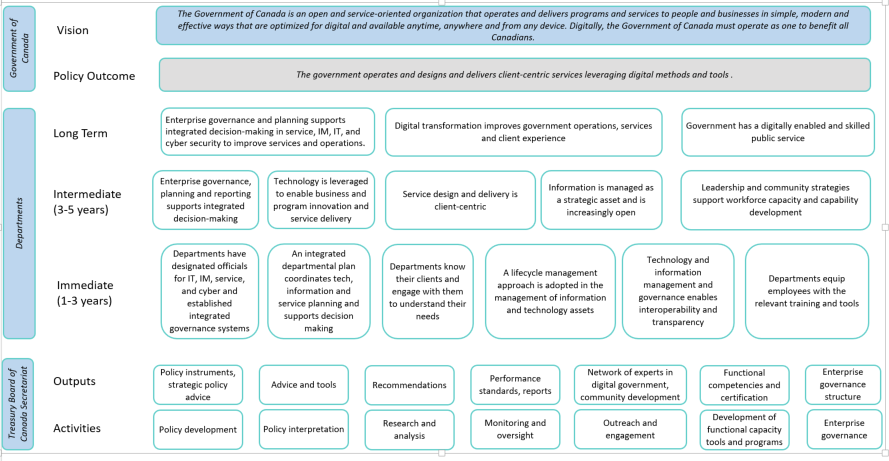

Integrated governance means that all pertinent officials from the different functional areas in the Policy – service design and delivery, information, data, technology and cyber security – are brought together at government-wide and departmental decision-making tables. This allows them to convey considerations related to their functional area and have them reflected at all stages of development and implementation.

At the government-wide level, a deputy-level committee has been established to provide advice and recommendations to the Secretary of the Treasury Board and the Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Canada on strategic decisions regarding:

- managing external and internal enterprise services, information, data, IT and cyber security

- prioritizing Government of Canada demand for IT shared services and assets

The CIO of Canada is responsible for providing advice to the Secretary and President of the Treasury Board of Canada on these matters, as outlined in the following requirements:

Requirements for the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) under the Policy

The Secretary of the Treasury Board of Canada is responsible for:

Establishing and chairing a senior-level body that is responsible for providing advice and recommendations, in support of the Government of Canada’s priorities and the Government of Canada Digital Standards, regarding:

Strategic direction for the management of external and internal enterprise services, information, data, information technology (IT) and cyber security; and

Prioritization of Government of Canada demand for IT shared services and assetsThe Chief Information Officer (CIO) of Canada is responsible for:

Providing advice to the Secretary of the Treasury Board of Canada and the President of the Treasury Board of Canada about:

Governing and managing enterprise-wide information, data, IT, cyber security, and service design and delivery;

Prioritizing Government of Canada demand for IT shared services and assets; and,Using emerging technologies and the implications and opportunities of doing so for the Government of Canada.

Providing direction on the enterprise-wide transition to digital government, including: regularly reviewing and updating the Government of Canada Digital Standards; managing information, data, IT, and cyber security; and, advising on enterprise-wide service design and delivery.

Establishing priorities for IT investments (including cyber security investments) that are enterprise-wide in nature or that require the support of Shared Services Canada (SSC).

At the departmental level, deputy heads are required to establish integrated departmental governance to ensure the efficient and effective integrated management of these functions within their organizations.

Requirement for departments under the Policy

Deputy heads are responsible for:

Establishing governance to ensure the integrated management of service, information, data, IT, and cyber security within their department.

1.2.2 Why is this important?

Integrated governance ensures that perspectives from all of the relevant functional areas are considered proactively in the development of government initiatives. This allows officials to draw connections between different functional areas and make decisions strategically in support of a more efficient, high-quality, and well thought-through suite of programs and services. It also ensures activities in each area of management are aligned with clear business outcomes (for example, service, operations). This approach allows decision-makers to identify issues at the outset or early in the process of any initiative to enable course correction.

Supporting the implementation of a government-wide approach to digital requires integrated discussions so that the focus is on:

- business needs, including improving services to clients

- ensuring the sustainability and security of technology (for example, replacing legacy systems)

- ensuring data and information are complete, available and usable, when needed.

1.2.3 Considerations in implementing the requirements

- All departments are different – whether in size, mandate, sector or nature of work – so consider developing a governance structure that is appropriate for the specific department.

- Consider leveraging existing bodies within the organization (either by integrating them or making clearer linkages between them), as long as their governance structure allows decision-making to be carried out in a way that is integrated with other areas of management.

- The scope of integrated governance should address how the department manages service, information, data, IT and cyber security (as required by the Policy).

- Consider including in the scope of the departmental governance committee, advice to the deputy head on:

- horizontal trends and issues that affect departmental service delivery and operations, to better support individuals’ and businesses’ access to services that are client-centric, trusted and secure;

- horizontal strategic and operational uses of information and data within the organization, consistent with privacy requirements and following government-wide direction; and,

- horizontal strategic and operational uses of IT (including cyber security considerations) within the organization, following government-wide standards and direction.

1.3 Integrated planning and reporting

1.3.1 Description and associated requirements

The three policy requirements under this theme focus on the integration of planning and reporting for service, information, data, IT and cyber security.

Requirement for TBS under the Policy

The CIO of Canada is responsible for:

Approving an annual, forward-looking three-year enterprise-wide plan that establishes the strategic direction for the integrated management of service, information, data, IT, and cyber security and ensuring the plan includes a progress report on how it was implemented in the previous year.

The Policy requires the CIO of Canada to produce an integrated government-wide plan that:

- provides overarching enterprise-wide direction for managing service, information, data, IT and cyber security

- is issued annually and covers the next three years

- includes a progress report that provides a measured assessment of how the plan for the previous year was implemented

Requirement for departments under the Policy

Deputy heads are responsible for:

Approving an annual forward-looking three-year departmental plan for the integrated management of service, information, data, IT, and cyber security, which aligns with the CIO of Canada’s enterprise-wide integrated plan, is informed by subject-specific plans or strategies as appropriate, and includes a progress report on how it was implemented in the previous year.

The Policy requires deputy heads of departments to produce an integrated departmental plan that:

- provides overarching direction for the integrated management of service, information, data, IT and cyber security within their organization

- is informed by subject-specific plans, such as a dedicated service, information management, data, IT, or cyber security plan as appropriate, where more specificity and detail may be required

- is issued annually and covers the next three years

- is aligned with the CIO of Canada’s enterprise-wide integrated plan

- includes a progress report that will provide a measured assessment of how the previous plan was implemented

Requirement for departments under the Directive

Departmental CIOs are responsible for:

Producing the departmental IT expenditure report and on-going Application Portfolio Management update reports.

This requirement mandates departmental CIOs to produce:

- a departmental IT expenditure report

- data to support the ongoing Application Portfolio Management program

1.3.2 Why is this important?

Integrating planning and reporting across service, information, data, IT and cyber security:

- supports effective planning and better decision-making by articulating clear and tangible instructions for departments

- enables assessment of government performance against various priorities such as service improvement, release of open information and legacy migration

- provides for a more holistic approach to planning and reporting, which allows key interdependencies to be identified, including identifying systems that have limited business value and opportunities to reallocate investments in areas that support service delivery

- ensures that client-centric services to Canadians are supported by establishing, measuring and assessing performance against targets

1.3.3 Considerations in implementing the requirements

Departments will be expected to provide integrated plans following instructions from TBS, once they become available. TBS, in collaboration with departments, will be developing additional and updated guidance and tools to set out expectations for integrated planning and reporting.

Integrated departmental plan

A departmental integrated plan is to:

- outline how service, information, data, IT and cyber security will be managed together within the department

- balance departmental priorities against the CIO of Canada’s government-wide plan that provides the strategic direction and priorities for the Government of Canada with respect to the same areas of management

Departments’ progress in achieving the strategic goals outlined in the CIO of Canada’s enterprise plan will be tracked, evaluated and reported on annually at the enterprise level. Departments, through their integrated plans, will detail how the enterprise approach will be implemented within their organization.

Departments’ integrated plans will be leveraged to support enterprise priorities, such as:

- improving services provided to Canadians

- providing sound information and data stewardship

- ensuring secure and sustainable IT infrastructure and systems

IT Expenditure Report

Departments will also be asked to produce an IT Expenditure Report, supplemental to the integrated departmental plan.

In 2011, the Comptroller General of Canada and the CIO of Canada jointly issued a request to some departments for information on departmental IT expenses. TBS asked those organizations to:

- use a “high-level” expenditure model to create a baseline for Government of Canada IT expenses, starting with data from 2009–10

- maintain this data for each fiscal year on an ongoing basis

Collection of such information has continued as the IT Expenditure Report, which collects departmental spending on IT by fiscal year and helps inform decision-making.

Context and guidance for departments on developing an IT Expenditure Report is available on the IT Expenditure GCwiki page (available only on the Government of Canada network).

Application Portfolio Management Program

Departments will also be asked to provide data to support the TBS Application Portfolio Management Program which will supplement the integrated departmental plan.

The TBS Application Portfolio Management Program aims to:

- improve the maturity of application portfolio management practices across government to provide a holistic view of the Government of Canada applications landscape, related risks and investments

- support government-wide strategies on the renewal and ever-greening of aging applications that are economical and that ensure continued services to Canadians

- direct investments towards government priorities, by implementing as part of investment planning, multi-year planning for applications that are interlocked with corporate risk

- populate Shared Service Canada inventories to help provide responsive and tailored client support

Context and guidance for departments on developing an Application Portfolio Management Report is available on the GCwiki Application Portfolio Management (APM) page (available only on the Government of Canada network).

Other considerations in implementation: broader alignment

In addition to ensuring integrated planning to manage service, information, data, IT and cyber security, other Treasury Board policies require deputy heads to ensure alignment with other areas of management, such as financial management and investment planning, including project management, procurement, materiel management and real property. For example, it is recommended that a department’s capacity for the following be considered in setting strategic direction, prioritization and impact:

- financial management

- investment planning

- procurement and project management

- capacity of service providers

- change management

1.4 Enterprise architecture governance

1.4.1 Description and associated requirements

Enterprise architecture (EA) is a conceptual blueprint that defines the structure and operation of an organization while considering and aligning business, information, data, application, technology, security, and privacy domains to support strategic outcomes. EA leads an organization toward an integrated and unified enterprise system that is better positioned to create business value and address organizational silos.

Governance for EA at the enterprise level is conducted through the Government of Canada Enterprise Architecture Review Board (GC EARB), which oversees the implementation of the EA direction for the Government of Canada. The objective of enterprise-level EA governance is to ensure that departmental vision and standards are aligned with Government of Canada EA requirements.

Requirements for TBS under the Policy

The CIO of Canada is responsible for:

Prescribing expectations with regard to enterprise architecture.Establishing and chairing an enterprise architecture review board that is mandated to define current and target architecture standards for the Government of Canada and review departmental proposals for alignment.

The Directive on Service and Digital outlines when departments must appear before the GC EARB and how to establish their own departmental architecture review board (DARB).

Requirements for departments under the Directive

The departmental CIO is responsible for:

Chairing a departmental architecture review board that is mandated to review and approve the architecture of all departmental digital initiatives and ensure their alignment with enterprise architectures. [Note that small departments and agencies are exempt from this requirement].

Submitting to the Government of Canada enterprise architecture review board proposals concerned with the design, development, installation and implementation of digital initiatives:

Where the department is willing to invest a minimum of the following amounts to address the problem or take advantage of the opportunity:

$2.5 million dollars for departments that do not have an approved Organizational Project Management Capacity Class or that have an approved Organizational Project Management Capacity Class of 1 according to the Directive on the Management of Projects and Programmes;

$5 million dollars for departments that have an approved Organizational Project Management Capacity Class of 2;

$10 million dollars for departments that have an approved Organizational Project Management Capacity Class of 3;

$15 million dollars for the Department of National Defence;$25 million dollars for departments that have an approved Organizational Project Management Capacity Class of 4;

That involve emerging technologies; That require an exception under this directive or other directives under the policy;That are categorized at the protected B level or below using a deployment model other than public cloud for application hosting (including infrastructure), application deployment, or application development; or

As directed by the CIO of Canada.Ensuring that proposals submitted to the Government of Canada enterprise architecture review board have first been assessed by the departmental architecture review board where one has been established.

Ensuring that proposals to the Government of Canada enterprise architecture review board are submitted after review of concept cases for digital projects according to the “Mandatory Procedures for Concept Cases for Digital Projects” and before the development of a Treasury Board submission or departmental business case.

Ensuring that departmental initiatives submitted to the Government of Canada enterprise architecture review board are assessed against and meet the requirements of Appendix A: Mandatory Procedures for Enterprise Architecture Assessment and Appendix B: Mandatory Procedures for Application Programming Interfaces.

1.4.2 Why is this important?

EA supports a coordinated approach by providing an integrated view of IT spending and priorities that will help the government optimize its IT investments. Enterprise architecture ensures better coordination, within and between departments, that:

- prevents duplicative spending

- increases cost efficiencies through sharing lessons learned, procurement vehicles, and investments

- increases interoperability

- provides more cohesive government services

- addresses security and privacy considerations

EA governance at the enterprise level ensures that all departmental digital initiatives that meet criteria of subsection 4.1.1.2 of the Directive on Service and Digital:

- are reviewed at the GC EARB

- align with Government of Canada EA standards (see the Directive’s Appendix A: Mandatory Procedures for Enterprise Architecture Assessment and Appendix B: Mandatory Procedures for Application Programming Interfaces)

1.4.3 Considerations in implementing the requirements

To ensure clear direction and guide departments on aligning with government-wide direction and strategies for EA, mandatory procedures are included in the Directive on Service and Digital in:

- Appendix A: Mandatory Procedures for Enterprise Architecture Assessment : provides an assessment framework to review digital initiatives to be used by DARBs and the GC EARB.

- Appendix B: Mandatory Procedures for Application Programming Interfaces : provides details on subsection A.2.3.10.3 of the Mandatory Procedures for Enterprise Architecture Assessment, which relates to the use of application programming interfaces to:

- allow communication between IT services

- enable interoperability

Departmental Architecture Review Boards

The Directive requires that the departmental CIO is responsible for chairing a Departmental Architecture Review Board (DARB) and submitting architecture review board proposals to the GC EARB. The composition of DARBs should reflect integrated governance for the department that touches on IT, IM and data, service and cyber security.

Making a Proposal to the GC EARB

- Conduct a self-assessment against the criteria in subsection 4.1.1.2 of the Directive on Service and Digital.

- If one or more of the criteria apply, the proposal is to be submitted to the GC EARB.

- Ensure that the proposal follows the review of concept cases for digital projects, before the development of a Treasury Board submission or a Departmental Business Case. Refer to the Mandatory Procedures for Concept Cases for Digital Projects and the graphical representation of the governance steps to be followed for digital projects.

- Ensure that the proposal meets the requirements of Mandatory Procedures for Enterprise Architecture Assessment and Mandatory Procedures for Application Programming Interfaces.

- Bring the proposal to your DARB for assessment, before submitting it to the GC EARB.

- Once the DARB has assessed the proposal, the presenter can complete the GC EARB Presenter Template and submit the proposal by email to the Enterprise Architecture Team in the Office of the Chief Information Officer at the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Once received, the proposal is reviewed by the Enterprise Architecture Team against the requirements of the Mandatory Procedures for Enterprise Architecture Assessment.

- Once reviewed, the Office of the Chief Information Officer EA team:

- provides feedback to the presenter on the proposal in advance of the presentation at the GC EARB

- briefs the GC EARB co-chairs

For more information, visit the GCwiki Enterprise Architecture Review Board web page (available only on the Government of Canada network), which includes information such as the GC EARB’s agendas, past sessions, and other useful links and resources.

Additional resources include:

- Enterprise Architecture Community of Practice (requires an account to access this content): discusses a range of topics related to EA in the Government of Canada and has subgroups for each of the EA layers, including:

- business architecture

- information architecture

- application architecture

- technology architecture

- security and privacy architecture

The group’s resources include:

- target architectures developed by departments (requires an account to access this content)

- a draft Government of Canada Service and Digital Target architecture (requires an account to access this content)

- GC Enterprise Architecture wiki.This page provides details on the various layers of EA.

1.5 Innovation and experimentation

1.5.1 Description and associated requirements

Implementing innovation and experimentation can be complex in a context where enterprise-wide standardization is prioritized to achieve increased interoperability and other government-wide outcomes, such as improved government services and operations.

In TBS’s Experimentation Direction for Deputy Heads: December 2016, experimentation is defined as “testing new approaches to learn what works and what does not work using a rigorous method.” This direction identifies possible features that an experimentation project could have, as well as potential innovative approaches, including tools and methods. In this direction, innovation is regarded as finding new ways to address problems. Experimentation is vital to innovation because turning an idea or concept into a meaningful reality must be tested before release.

At the government-wide level, the CIO of Canada plays a role in facilitating this process by providing tools and guidance in support of innovation and experimentation, including establishing guidance on open-source and open-standard applications, and agile application development.

Requirements for TBS under the Policy

The CIO of Canada is responsible for:

Facilitating innovation and experimentation in service design and delivery, information, data, IT and cyber security.

Establishing guidance to support innovative practices and technologies, including open-source and open-standard applications, and agile application development.

At the departmental level, the process of providing the appropriate level of support to take an idea, refine it, experiment with it and turn it into a real solution is what this requirement is about.

Requirement for departments under the Policy

The deputy head is responsible for:

Providing support for innovation and experimentation in service, information, data, IT and cyber security.

1.5.2 Why is this important?

Technologies are constantly changing and the operational necessities of managing an organization present little opportunity to research and implement new technologies. Therefore, deputy heads need to support specific activities to review, assess and potentially adopt new methods to better support departmental priorities and improvements to services and operations in the long run.

The benefits of exploring innovation and experimentation include:

- finding new ways to address persistent problems that traditional approaches have failed to solve

- generating evidence to learn what works and it inform decision-making

- delivering services to the public using tools that are modern and effective to meet client expectations

- empowering employees to bring forward new ideas

- keeping pace with rapidly evolving technological changes and avoiding the use of outdated tools

1.5.3 Considerations in implementing the requirements

The government is committed to devoting a fixed percentage of program funds to experimenting with new approaches and measuring impact. However, additional methods that deputy heads can use (based on their department’s size, mandate and other factors) include:

- internal activities (e.g., Dragons’ Den-style events, hackathons)

- supporting structures (e.g., innovation hubs)

- employee-focused activities (e.g., awareness, time allotments, training)

In providing support for innovation and experimentation, departments could consider:

- developing proofs of concept and pilot projects as a way to learn quickly before launching on a full scale

- creating an environment that supports cross-departmental collaborations

- creating a research and development team with operational resources frequently rotating in and out

- developing an environment that allows for the isolated execution of software or programs for independent evaluation, monitoring or testing, without affecting the application, system or platform on which they run (sandbox environments) to enable the safe incubation of disruptive projects

- using fictional data (data created from scratch that do not include personal information and that do not represent or identify Canadian citizens) in innovation and experimentation solutions to eliminate risks of information exposure or privacy breaches

- using modern and agile practices in software development to reduce implementation timelines

- leveraging open-source and open-standard applications to avoid duplicating efforts and allow for community-based improvements

- partnering with external stakeholders such as universities to establish events such as hackathons (using open data) to help innovate

Pilots and proof of concepts can be submitted to the GC EARB for review and assessment. GC EARB provides recommendations on new processes and technology when conducting assessments. Subsection 1.4 of this guideline has more information on GC EARB assessments.

In order to share and promote innovation and experimentation broadly within the Government of Canada, and to showcase successful practices and learn from challenges, departments should incorporate activities for their innovation and experimentation projects into their departmental planning processes.

Innovation and experimentation activities, as for any other activities undertaken in departments, must comply with all related laws and Treasury Board policies, including requirements for privacy protection, security and accessibility.

Departments should use fictional data instead of collecting, using or disclosing personal information in an experimental context. Contact your institution’s Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) office to discuss the requirement for a Privacy Impact Assessment, as required by the Directive on Privacy Impact Assessment. Subsection 3.6 of this guideline has more information on specific considerations related to privacy and protection of personal information.

It is also important to prioritize security at the outset of innovation and experimentation activities. For more information on security considerations, see subsection 4.1 of this guideline. In the context of cloud, additional security controls may need to be considered in order to satisfy departmental requirements. For more information on security considerations related to cloud services, see subsection 4.3 of this guideline.

There is also an opportunity to experiment with new ways of enabling accessibility across the government, whether it is related to accessible information and communication technology or creating accessible documents from the outset. See subsection 3.5 of this guideline for more information on accessibility requirements.

In line with the requirement of the CIO of Canada to support innovative practices and technologies, including open-source and open-standard applications and agile application development, further guidance on Open Source Software and an Open First Whitepaper are available for departmental use. Departments that are interested in additional research and guidance for open source in government can join the TBS-led FLOSSING (requires an account to access this content) community of practice.

2. Client-centric service design and delivery

- 2.1 Client-centric services

- 2.2 Client feedback and satisfaction

- 2.3 Online services

- 2.4 Real-time application status

- 2.5 Service inventory

- 2.6 Availability of service inventory on the open governmental portal

- 2.7 Service standards

- 2.8 Review of service standards

- 2.9 Real-time service performance information

- 2.10 Service review

Every day, the Government of Canada delivers a broad range of services to Canadians. Excellence in designing and providing services promotes confidence in government and contributes to the efficient and effective achievement of public policy goals and better services for Canadians.

In an effort to continually improve its services, the Government of Canada has adopted a vision where:

- client needs and feedback are at the centre of service design and delivery

- services are simple, seamless, transparent, digitally enabled, and available anytime and anywhere

Among the expected outcomes of the Policy on Service and Digital is the development of departmental capacity to facilitate client-centric service design and delivery.

This section outlines the following key components:

- implementing client-centric service design, delivery and improvement

- maximizing the availability of end-to-end online services to complement all service delivery channels

- establishing a departmental service inventory that is updated annually

- developing service standards, related targets and performance information

- undertaking service reviews

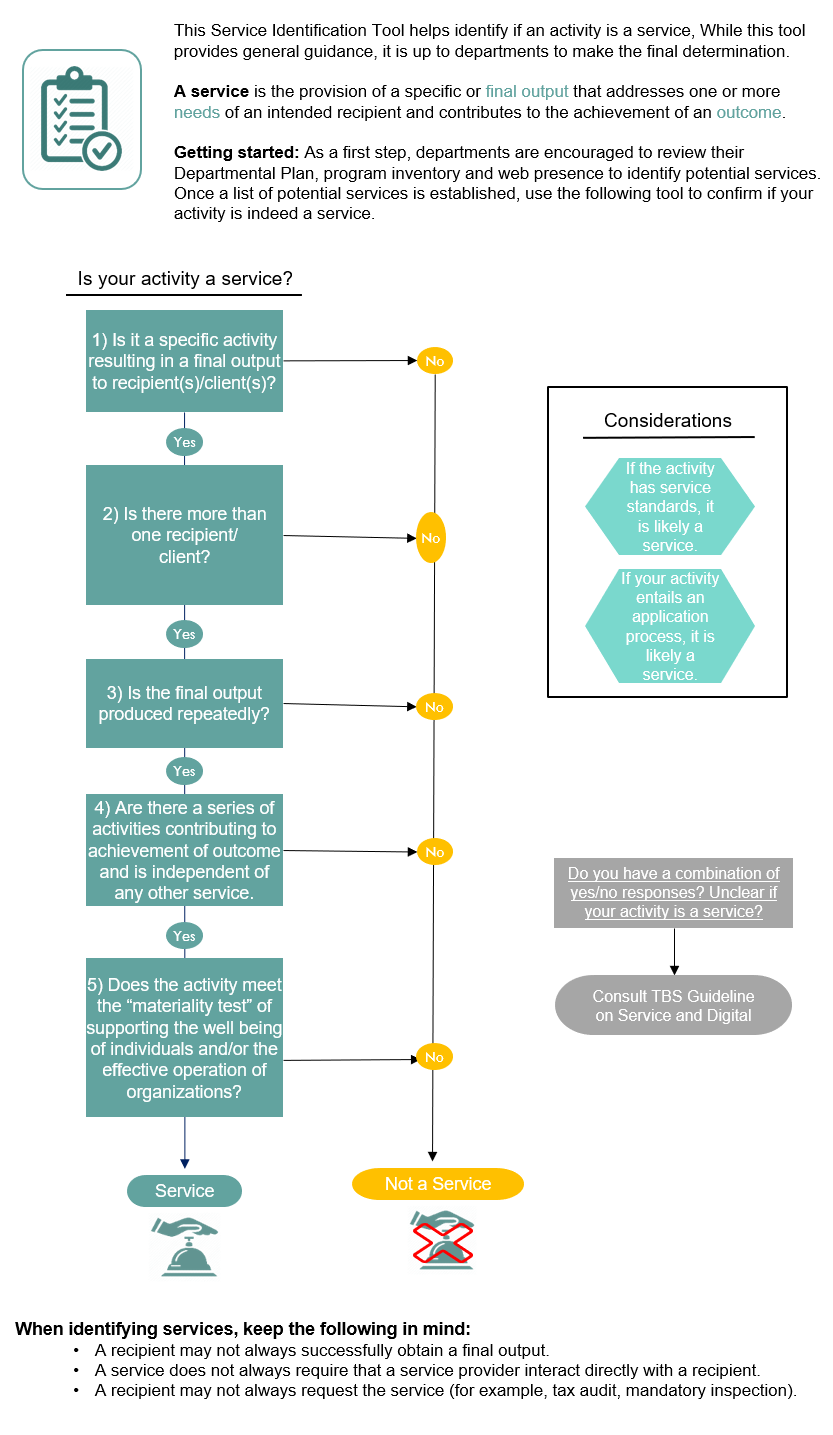

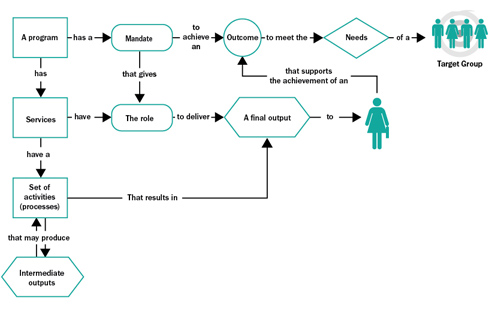

Appendix C contains information on service definition, identification and types of services.

This section of the guideline replaces the guidance provided in the Guideline on Service Management, which was developed in support of the Policy on Service.

2.1 Client-centric services

2.1.1 Description and associated requirements

Client-centric services focus on addressing client or user expectations, needs, challenges and feedback. Such services create a positive experience for the client or user and consider several factors, such as:

- access

- inclusion

- accessibility

- security

- privacy

- simplicity

- choice of official language

A service-oriented government puts clients and their needs as its primary focus. A central component of this approach is understanding the needs of clients (whether external or internal to government) and building services around clients rather than concerns about organizations or silos.

Requirement for departments under the Policy

Deputy heads are responsible for:

Ensuring the development and delivery of client-centric service by design, including access, inclusion, accessibility, security, privacy, simplicity, and choice of official language.

2.1.2 Why is this important?

Placing clients at the centre of the service design and delivery process allows government to better understand the public’s needs, and tailor services accordingly. A successful digital government continually improves how it designs and delivers services to improve the lives of its citizens, while maximizing the opportunities presented by information and technology to do so.

2.1.3 Considerations in implementing the requirement

When designing services, departments should consider several factors related to client-centric service, including the following:

Access

Clients increasingly expect to access the services they need, when and where they want, whether it be online, by phone or in person. This requires an omni-channel approach for all services in order to:

- offer Canadians an integrated client experience

- enable the modernization of Government of Canada services

- provide a barrier-free service experience for persons with disabilities

Departments can leverage technology and automation across all service delivery channels, including in-person services and call centres, to increase their efficiency and improve the client experience.

Examples

- OneGC is the enterprise approach to enable seamless service delivery through interoperable systems, data-sharing and greater integration between services. OneGC is the umbrella under which common technology solutions and experimental service initiatives are pursued, in support of the digital government vision, where services are optimized for digital and are available anytime, anywhere and from any device.

- The use of digital identity to identify and authenticate users and provide them with more seamless and secure enrolment and access to online services. See subsection 4.7 of this guideline for more information.

Inclusion

As the Government of Canada builds its capacity to offer more efficient client-centric services, there is an opportunity to bring about a culture shift to foster greater social inclusion. Such inclusion improves the participation of groups in society, particularly for people who are disadvantaged, by enhancing opportunities, access to resources, greater participation and respect for rights. Further information is available in see the Inclusive Design Guide prepared by the Inclusive Design Institute (IDI).

Accessibility

When designing services, departments are to ensure that they are barrier-free for all clients by making them inclusive, accessible by default and usable by the broadest range of employees and the public without special adaptation. Footnote 2 See subsection 3.5 of this guideline for more information on specific considerations related to accessibility.

ESDC’s Accessible Client Service Centre of Expertise has been working with partners to develop tools to support ESDC become more accessible. These tools can be used more broadly to support the government-wide effort.

Security

When designing services, departments are to:

- consider today’s dynamic operating environment, which is increasingly global and features:

- a highly mobile workforce

- shared IT

- shared service delivery

Building cyber security into any government technology strategy is essential to ensuring continuity of service and safeguarding citizens’ private information. Consolidated programs, online end-to-end services and “tell us once” approaches increase the importance of cyber security, as information that is more consolidated or connected can intensify the potential impacts of security breaches, including privacy breaches (for example, a privacy breach for one program could put client information from many programs at risk). See subsection 4.6 of this guideline for more information on specific considerations related to cyber security.

Privacy

The requirements of the Privacy Act, the Privacy Regulations and associated policies for the effective protection and management of personal information must be integrated throughout the design and delivery of services and systems. These requirements include:

- limiting the collection of personal information to only what is directly related to delivering a service

- ensuring that clients are notified in advance about why their personal information is being collected and how it will be used

- ensuring that personal information is used only in ways that have been communicated to clients

- sharing personal information only as permitted by law

- keeping personal information only for as long as required

See subsection 3.6 of this guideline for more information on specific considerations related to privacy.

Simplicity

Whether services are provided in person, by telephone or online, it is important that they be simple so that they are easy to use for the client or user. Various factors contribute to this experience, including using:

- clear language

- appropriate formats

- simplified interaction processes

- user-friendly guidance (text boxes, YouTube videos, pamphlets) when necessary

Official languages

When designing and delivering services, departments must:

- support activities that benefit members of both official language communities

- respect the obligations of the Government of Canada as set out in the Official Languages Act, including ensuring that services are made available in both official languages

- comply with the Policy on Official Languages.

2.2 Client feedback and satisfaction

2.2.1 Description and associated requirements

Client feedback is information directly from recipients of services about their satisfaction or dissatisfaction with a service or product. It is a key part of service design and improvement and can take several forms, including:

- in-service client feedback

- client satisfaction surveys

- user experience design and testing

- consultations

Requirement for departments under the Directive

The designated official for service, in collaboration with other officials as necessary, is responsible for:

Ensuring that client feedback, including in-service client feedback, client satisfaction surveys and user experience testing, is collected and used to improve services according to TBS direction and guidance

2.2.2 Why is this important?

Client feedback is a critical input into ensuring that services meet the needs of clients and to support continual improvement. It serves several key purposes, including:

- identifying areas of service design and delivery that require improvement

- providing an opportunity to establish trust relationships between clients and the organization by responding to client needs in addressing service-related challenges

- increasing operational efficiency and effectiveness, and improving service outcomes, by identifying and addressing systemic service delivery issues

- contributing to the overall evaluation of client satisfaction with the organization’s services

2.2.3 Considerations in implementing the requirement

- Client feedback mechanisms can include various formal or informal methods or tools to collect feedback from clients and resolve service issues not related to decisions or appeals

Examples of feedback channels include:

- an ombudsman

- a generic departmental email or social media account

- questionnaires during service delivery

- the use of analytics tools

Client feedback mechanisms allow departments to receive and manage input from clients and involve recording, processing, responding to and reporting on the input received. These mechanisms are used after a service or product has already been launched to support improvements on the service or product. They are distinct from user experience design, which supports the development of services and products that provide meaningful and relevant experiences to users.

Client feedback mechanisms do not replace independent measures of service performance such as service standards or internal operational performance measures (for example, completion rates, time to completion of application, abandoned applications or calls, etc).

When services are delivered by a group of partners (such as Canadian or international organizations, or other levels of government such as provinces, territories and municipalities), departments are to work with them to develop and process client feedback.

Feedback mechanisms are used to manage a broad range of client experience information and usually employ several methods across all service delivery channels (in person, telephone and online), both prompted and unprompted. For example:

- feedback mechanisms that involve prompting users for input include offers to participate in an exit survey

- an unprompted method could include a “contact us” section that includes a web link, generic email and/or telephone number to contact the department

When departments seek client feedback, they should consider the Government of Canada’s public engagement principles.

Information received through the feedback mechanism can be classified into two broad categories:

- General feedback used to improve services, including future service improvement work plans

- More specific feedback or complaints on service delivery issues that are likely to require interaction or follow-up with a client, with varying degrees of urgency

Addressing service issues

A service issue refers to a challenge that a client is experiencing at any point in the process of receiving a service. It does not relate to recourse related to a decision or a formal appeal process.

Resolving service issues quickly, even when they are minor, is important to providing an overall positive service experience for the client. How quickly these issues are resolved will depend on their complexity and the operational circumstances of the organization. Examples of service issues include:

- seeking clarification on what information is required to submit a complete application

- overcoming difficulty with a web page, registering or authenticating a departmental account, or submitting an application

- enquiring about the status of an application

Service issues are routinely raised with client service officers during normal client interactions and can usually be resolved quickly, to the clients’ satisfaction or understanding during the initial contact. To the extent possible, these interactions should be recorded to inform service management improvement in a manner consistent with section 3.6 (Privacy and protection of personal information) of this Guideline.

Determining whether an issue identified by a client is eligible for consideration under a particular client engagement mechanism can help avoid wasting resources on a misunderstanding or a wrongly directed concern. For example, clients should be directed to use general feedback channels to raise service delivery issues and to contact an ombudsman (or similar mechanism) to make a formal complaint or to dispute the outcome of a service request, such as ineligibility for a benefit.

A client’s perceptions of service delivery may be influenced by the outcome of the service. For example, even if the delivery of the service met or exceeded established service standards, a client may perceive the experience as negative if the outcome is negative, such as a denial of a benefit for not meeting eligibility criteria, or being informed of an unfavourable tax assessment. In these cases, the outcome of the transaction is influencing the client’s satisfaction with the service.

Depending on the service, a single method may be appropriate for collecting feedback and resolving service issues.

When there is a large volume of services and transactions, a specific office dedicated to client feedback and service resolution, such as an office of client satisfaction, could be considered.

Examples of client feedback methods include:

- generic links for comments, compliments and complaints on the organization’s web presence

- a web pop-up during or after service delivery interactions

- a service agent recording verbal input during an in-person or telephone visit

- an electronic kiosk at in-person centres where feedback can be submitted

- a service exit survey

- an external stakeholders reference group

- public opinion research (for example, client satisfaction surveys)

Examples of methods to resolve client-service issues include the following:

- an online live chat function

- online co-browsing with a service agent

- a telephone or in-person conversation with a service agent

- a departmental response to the client via email

- reference to a repository of frequently asked questions

Characteristics of effective client feedback mechanisms

- Easily accessible: Feedback mechanisms should be easily identifiable by clients, and their availability should be actively promoted across all service channels. Clients who wish to provide feedback or require assistance to resolve a service issue need to know how to provide it and to whom, and this information should be readily available and clear. Consider the following questions:

- Does the department proactively provide information to clients about how to provide feedback through all service delivery channels? How is this information disseminated?

- Are there suitable arrangements to allow people with disabilities to provide feedback or raise issues?

- Is guidance on using the feedback mechanisms available for clients?

- Is the format and language used to collect feedback easily understandable by the service’s target clients?

- Are written procedures or guidance on feedback and mechanisms to resolve issues available to employees?

- Does the department review guidance and feedback procedures regularly?

- Has the department designated staff to help address client feedback issues?

- Do the procedures set out clear responsibilities for designated staff?

All employees who deal with clients regularly should receive training in service excellence, including how to handle various issues. Such training could include instruction in negotiation, alternative dispute resolution, and dealing with difficult people. Consider the following:

- Do procedures allow employees to provide immediate resolution, where appropriate?

- If employees cannot deal appropriately with an issue immediately, do the procedures identify the key steps for conducting a full review and for providing a full final reply?

- Are there standardized procedures for dealing with various types of issues and for each step in responding to clients, such as acknowledgment, interim reply and final reply?

- Does the department’s client relations management system allow employees to access information about an issue quickly?

- Has the department made service improvements after assessing issues raised by clients?

- Has the department released open data and information on feedback received and improvements made?

- timeliness

- courtesy

- ease of access

- ease of completing the transaction

2.3 Online services

2.3.1 Description and associated requirements

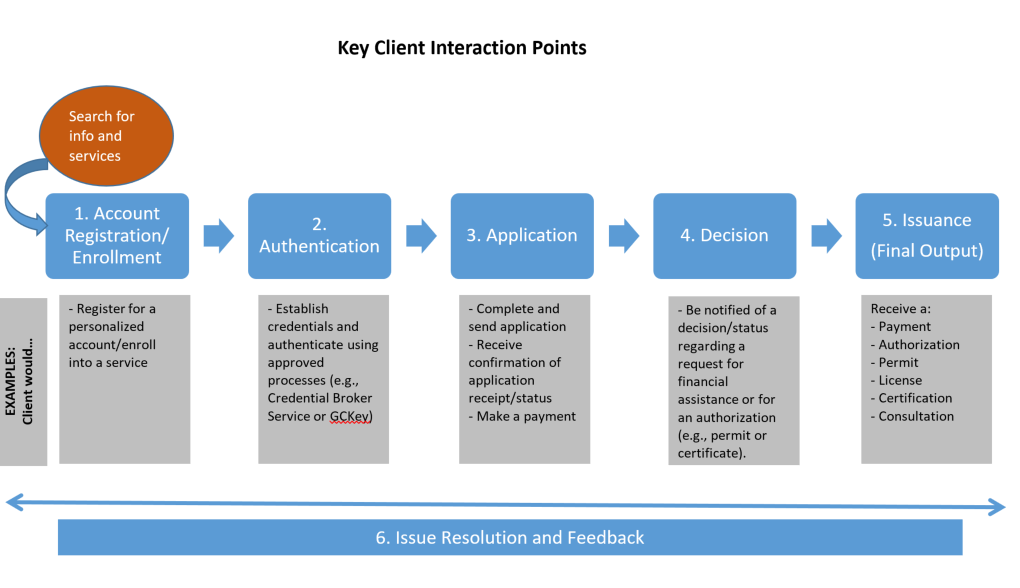

The Policy on Service and Digital defines online services (sometimes referred to as e-services) as services available on the Internet from beginning to end, without the client having to move offline to complete a step in the process. These services include the ability to receive a service online from the application stage, to the receipt of the final output and the provision of feedback. The final output may not be delivered online in all cases, as it may be a material document, such as a passport, a certificate or other item. However, departments are encouraged to consider the possibility of providing the final output online as well.

In instances of third-party delivery, departments have to incorporate online requirements into their contracts or agreements, as compliance with the Policy on Service and Digital remains necessary in those situations.

Requirement for departments under the Policy

Deputy heads are responsible for:

Maximizing the online end-to-end availability of services and their ease of use to complement all service delivery channels.

2.3.2 Why is this important?

Jurisdictions within Canada and around the world are increasingly focusing their efforts on delivering a better online service experience that clients want to use. Canadians and businesses have been clear that they expect online government services that:

- are accessible, fast and personalized

- respect privacy

- are secure

Online services are convenient for many clients and are significantly more cost-effective than services delivered through in-person or telephone channels.

It is important to pursue holistic and integrated online delivery of services. Requiring clients to download and print an online PDF file, complete it, and send it to a Government of Canada office by fax or email is considered to be “out of band” and not an online service. Moreover, this is not what clients expect as an online service and is inefficient.

2.3.3 Considerations in implementing the requirement

Considerations

- When establishing plans to increase the proportion of online services, consider:

- starting with the department’s services that are in highest demand and broadening the scope over time based on key factors such as volume of service, cost or benefit, and risk

- collaborating with key partners, such as the department’s CIO, its web senior departmental official, and other Government of Canada institutions that offer similar services

- Ensuring that privacy- and security-related considerations are addressed at the design stage. For more information, refer to subsection 4.1 of this guideline.

- whether the new system will collect and use personal information

- whether a Privacy Impact Assessment needs to be completed (the assessment will address how the service will respect the requirements of the Privacy Act)

- websites and web applications for mobile devices

- layout and design specifications for websites, web applications and device-based mobile applications

- a blueprint for how content on Canada.ca is to be organized

- templates and guidelines for departments to rework, develop and harmonize content as they prepare to migrate their content to the Managed Web Services platform and decommission their URLs

- information architecture requirements, which are key to effectively align the implementation of the Managed Web Services platform

When designing online services, consider the use of application program interfaces (APIs) as a means to facilitate this work. Refer to subsection 3.3 of this guideline for further details.

User engagement

User engagement promotes awareness among clients of the availability of online services and the benefits of accessing and using them, with the ultimate goal of increasing uptake. When engaging users on online services, consider:

- Incorporating user engagement into departmental integrated plans. Departments can articulate their engagement approaches or priorities within service management plans or other corporate planning documents.

- Engaging the departmental outreach and communications groups. They can provide valuable insight and advice on outreach activities and can coordinate these efforts with any other related communications initiatives for maximum impact.

- Explaining the benefits of online services to clients. Making clients aware of the time-saving and potentially cost-saving benefits of online services provides incentive to use online channels over other channels that are less efficient.

- Ensuring that the organization’s online services are secure and working properly. Doing so will increase the likelihood that those who use online services have a positive experience and return in the future. It can take only one negative experience for clients to choose not to use the organization’s online services, and possibly other government online services. Refer to subsection 4.6 of this guideline for other considerations related to cyber security.

- Limiting service information exchanged to the minimum necessary. Refer to subsection 3.6 of this guideline for information about privacy considerations.

- Addressing a diverse audience. Clients who are already tech savvy will likely migrate to online services as soon as they are aware they exist. However, other clients may need prompting since not all clients can be reached in the same way or through the same communications medium. Use a variety of platforms and methods (by telephone or in person) to raise awareness. Maintain alternate service delivery channels where appropriate so that clients have choices.

Key elements of a user-engagement approach

- A client-centric approach to online services: Ease of use is essential to the success of online services. Good user design, based on actual testing with users, followed by clear and thorough explanations on how to access and use available online services, will help increase their use. Instructions and guidance should be tailored to a wide range of clients, taking into account literacy levels, language and other factors.

- A client-centric multi-platform awareness campaign: In order to effectively migrate clients to online services, clients must be aware that this option is available and be aware of its benefits. Promoting awareness of the availability of online services should be done through all existing delivery channels, and can include using correspondence or reminders when providing services in person or through the telephone channels. Departments may wish to promote the benefits of using online services, such as the added convenience a service may offer, or the reduced time it would take to complete an application. These benefits may be communicated in real time, while the client is seeking a service through another channel (by telephone or in person).

- A measurement plan to assess areas of success and weakness: It is important to know the extent to which clients are using online services. Engaging with users can increase online service uptake.

- Limitations of online services: Beyond legal or security considerations, the online availability of services may not be practical from a cost or benefit perspective or because of other considerations such as technical feasibility. A particular intermediate activity of a service may not be available online under specific circumstances. In such cases, other channels may be required. The online availability of services requires taking a client-centric approach, and clients should be given the option to revert to the online channel once an activity that requires a different delivery channel has been completed.

2.4 Real-time application status

2.4.1 Description and associated requirements

Real-time application status refers to information on the current standing of a client’s request for a service or product.

Requirement for departments under the Directive

The designated official for service, in collaboration with other officials as necessary, is responsible for:

Ensuring that newly designed or redesigned online services provide real-time application status to clients according to TBS direction and guidance.

2.4.2 Why is this important?

Just as some clients expect to be able to complete the government’s authenticated external services online from end to end, they also expect to have access to real-time information on the state of their request or application. When accessing government services, clients need the most up-to-date information to make informed decisions. Providing such information facilitates openness and transparency of government processes in providing services and contributing to client satisfaction.

2.4.3 Considerations in implementing the requirement

This requirement applies only to a limited number of departmental services, which can be identified using the following cascading questions:

- What are the departmental services?

- Which of those services are external services?

- Which of those external services require the client to authenticate themselves in order to apply for or receive the service?

- Which services involve a request and a decision?

- Which services should be prioritized for this functionality? Consider prioritizing high-volume, high-impact services.

When providing real-time application status, consider the following key elements:

- a clear process for clients to receive an update or their application status on the department’s website

- access to service and action history (date, actions)

- access to any key messages or advisories related to the service

Following are examples of departments that provide application services in real time:

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

2.5 Service inventory

2.5.1 Description and associated requirements

A service inventory is a catalogue of services that provides detailed information about a department’s services based on a specific set of elements (for example, type, channel, client and volume). It contains information, known as data elements, that enables organizations to better know, understand and more strategically manage their portfolio of services.

Requirement for departments under the Policy

Deputy heads are responsible for:

Approving the department’s service inventory and annual updates.Requirement for departments under the Directive

The designated official for service, in collaboration with other officials as necessary, is responsible for:

Developing and annually updating a departmental service inventory according to TBS direction and guidance.

2.5.2 Why is this important?

When used effectively, a service inventory can be a useful tool to manage services. A service inventory also demonstrates an organization’s commitment to transparency and to service excellence. Using a service inventory has several benefits:

- it provides a snapshot of departmental services and related data, which in turn can support strategic management and decision-making

- it can help determine the resources required for service delivery (for example, staffing, facilities, IT and information management)

- it facilitates performance reporting by linking services to internal performance indicators and external service standards

- it supports the identification of opportunities to create efficiencies through consolidating and standardizing services or the constituent activities or processes within the department and across the Government of Canada

Individual departmental service inventories:

- can be updated via the Government of Canada Service Inventory data collection tool

- have been posted annually on the Government of Canada’s open government portal since July 2018

Publishing service inventories annually supports a departmental data-driven culture that is open and transparent.

2.5.3 Considerations in implementing the requirements

Identifying services

As a first step, departments can review their annual Departmental Report, Program Inventory and website to identify a list of the department’s services. Services could include typical external services that most departments offer, such as public enquiries and access to information and privacy requests. Once a list of potential services is established, use the Service Identification Tool described in Appendix C of this guideline to confirm whether the activities undertaken are indeed services. You can also refer to the definition of services in Appendix C and to the instructions below on developing a service inventory.

After this assessment, if your department concludes that it doesn’t provide any services, it must submit a declaration from the deputy minister to TBS that indicates the following:

- the department does not offer any services, as defined by TBS direction and guidance

- the department understands that the public-facing GC Service Inventory will show that the department does not offer any services

This declaration can be revisited regularly, and the organization should notify TBS when the declaration is no longer accurate, or upon TBS’s request.

Best practices for developing a service inventory

- Prepare to develop a service inventory:

- identify a champion at the senior management table

- identify a departmental lead or coordinator

- identify key contributors in the department (branches/sectors)

- develop a plan with key activities and timelines

- convene an information session with contributors to kick off data collection within the organization

- read the Policy on Service and Digital, the Directive on Service and Digitaland related policy instruments and guidelineson TBS’s website

- review the Service Identification Tool (see Appendix C of this guideline)

- verify for any updates on the Directive or guidance from TBS

- review your Departmental Plan, Program Inventory and website to prepare a draft list of services

- work with departmental partners to confirm services and related data elements

- become familiar with TBS’s data collection website to ensure that data collected aligns with the data fields required

- seek approval from your deputy head and information management senior official to allow publication on open.canada.ca

- use the login credentials sent by TBS to access the data collection website

- keep the department’s service inventory evergreen by updating it regularly

Key components of a service inventory

A service inventory includes a number of data elements, such as the following:

- service name

- service type

- special designations

- URL to access the service

- link to program inventories

- client type

- volume of transactions

- service standards and related performance information

- use of a business number or a social insurance number

- service fees

- online availability

A service inventory template, which identifies the full set of required data elements and related definitions, can be found on the GC Service Community page (requires an account to access this content).

You will need to input your departmental data via a web-based tool (requires an account to access this content) launched by TBS.

Although departments and agencies are required to review data elements in all fields annually, some fields will remain static year over year.

Some key points to consider when developing and updating a service inventory:

- The information in a service inventory should be verified and be consistent with data contained in a departmental Performance Information Profile (PIP) and other planning documents (for example, Departmental Plan and departmental data strategy).

- It is important to keep your service inventory evergreen by updating it on a regular or annual basis. Such updates are essential in order for your service inventory to accurately indicate the services provided by your department.

- It is also important that your department identifies:

- the custodian(s) of the inventory

- most recent revision date

- other important information (e.g., where to find information relating to the Privacy Impact Assessment for the service) that can serve as a reference point for those using or managing this information in the future.

Service name considerations

When naming a new service or revising an existing service name, consider the following:

- be concise and use plain language

- use names that are easily identifiable and relevant to the clients it serves (for example, “Call Centre,” “Complaints”)

- avoid using acronyms as part of the service name

- ensure that the service name is consistent with names used in the departmental or Canada.ca website and departmental reports, including the service inventory

- avoid labelling the service with the name of a branch or sector, unless necessary

- avoid including the words “process,” “program,” “service” or “activity” in the service name, unless required to align with a legislated or policy requirement

2.6 Availability of service inventory on the open governmental portal

2.6.1 Description and associated requirement

The Directive on Service and Digital requires departments to make their service inventory available through the Government of Canada Service Inventory, a consolidated database of Government of Canada services and related performance information open to the public via the open government portal.

Requirement for departments under the Directive

The designated official for service, in collaboration with other officials as necessary, is responsible for:

Working with TBS to make the departmental service inventory available through the Government of Canada open government portal according to TBS direction and guidance.

2.6.2 Why is this important?

The requirement to have departmental service inventories on the open governmental portal:

- provides open and transparent access to Government of Canada service information to departments, central agencies, academia and the public

- facilitates government-wide performance reporting

- supports the Government of Canada strategic management and decision-making

2.6.3 Considerations in implementing the requirement

As specified in the Directive on Service and Digital, the designated official for service, in collaboration with other officials as necessary, is responsible for:

- ensuring that service inventory data submitted to TBS is accurate

- working with TBS to revise the departmental service inventory for government-wide consistency for the purposes of release on the open government portal

Departments remain responsible for the accuracy of their data, and TBS is the custodian of the service inventory data for publishing purposes.

Timing

Although departments can update their service inventories at any time, they will typically collect data for the previous fiscal year during the summer, in time for TBS’s review and publishing on the open government portal in the fall.

Link to other requirements and policies

Service inventories must link to other requirements and policies, including:

- requirements 4.3.2.8 and 4.3.2.9 of the Policy on Service and Digital to release information and data on the open government portal (refer to subsection 3.4 of this guideline for more information)

- subsection 6.2 of the Directive on Open Government, which requires that open data and open information is released in accessible and reusable formats via Government of Canada websites and services designated by TBS

- the Policy on Results

2.7 Service standards

2.7.1 Description and associated requirement

A service standard is a public commitment to a measurable level of performance that clients can expect under normal circumstances when requesting a service. The term “normal circumstances” refers to the expected level of supply and demand for regular day-to-day service operations. Such operations differ from special circumstances where regular service standards may not apply (for example, circumstances that are typically not within the organization’s control, including holidays, natural disasters or other emergency situations).

Requirement for departments under the Policy

Deputy heads are responsible for:

Ensuring services have comprehensive and transparent client-centric standards, related targets, and performance information, for all service delivery channels in use, and this information is available on the department’s web presence.

2.7.2 Why is this important?

Service standards reinforce government accountability by making performance transparent. They also increase the confidence of Canadians in government by demonstrating the government’s commitment to service excellence. They are integral to good client service and to effectively managing performance, and can clarify expectations for clients and employees, drive service improvement, and contribute to results-based management. Service standards also help clients make time-sensitive, important decisions about accessing services and other expectations relating to services.

2.7.3 Considerations in implementing the requirement

Key components of this policy requirement include:

- scope: applies to all services where there is a clear and specific recipient

- channels: service standards must be developed for all service delivery channels, as applicable (for example, in person, telephone and online)

- comprehensiveness: includes access, timeliness, accuracy and real-time performance

- consistency: proposes a common approach to articulating standards and measuring their fulfillment

- transparency: focuses on what, how, where and when to publish information