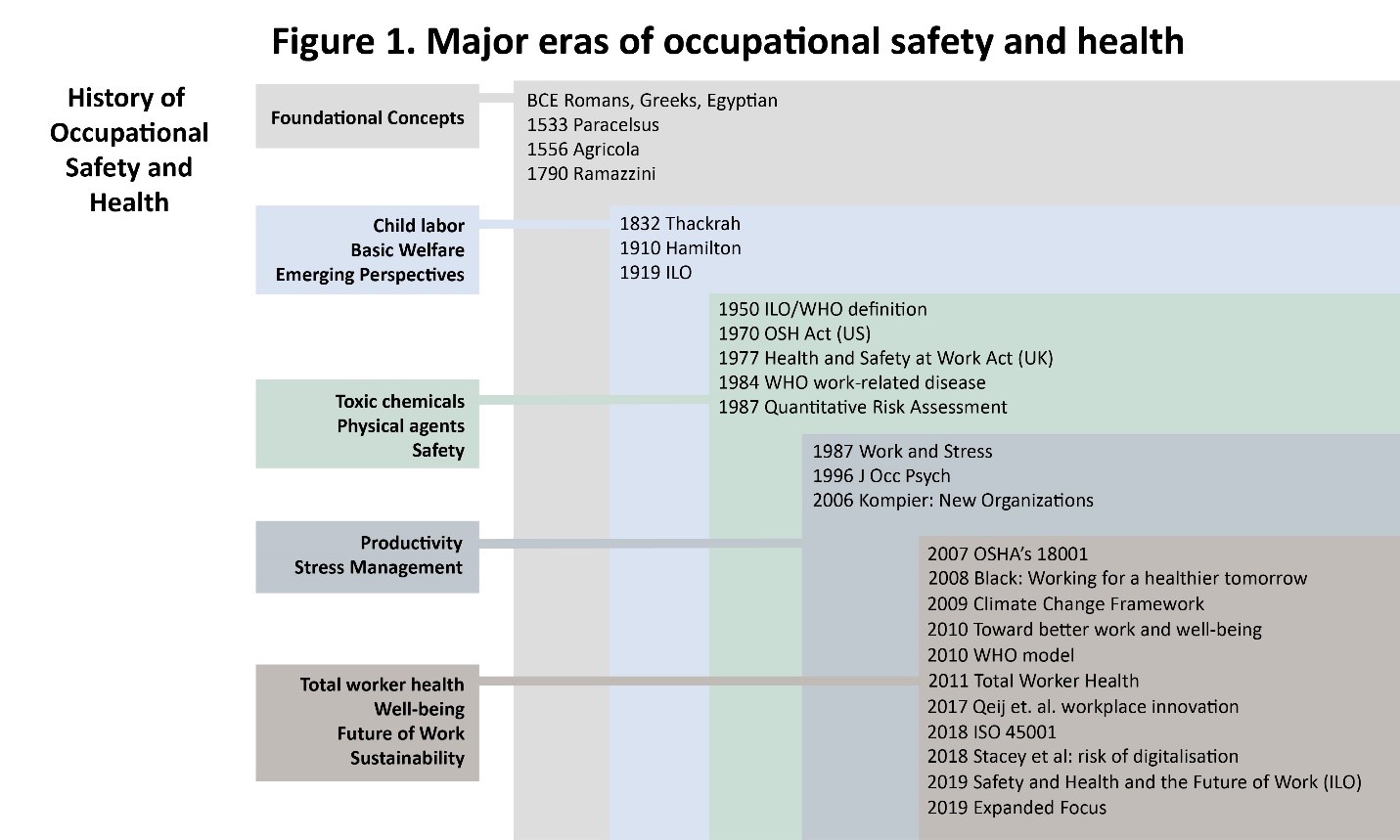

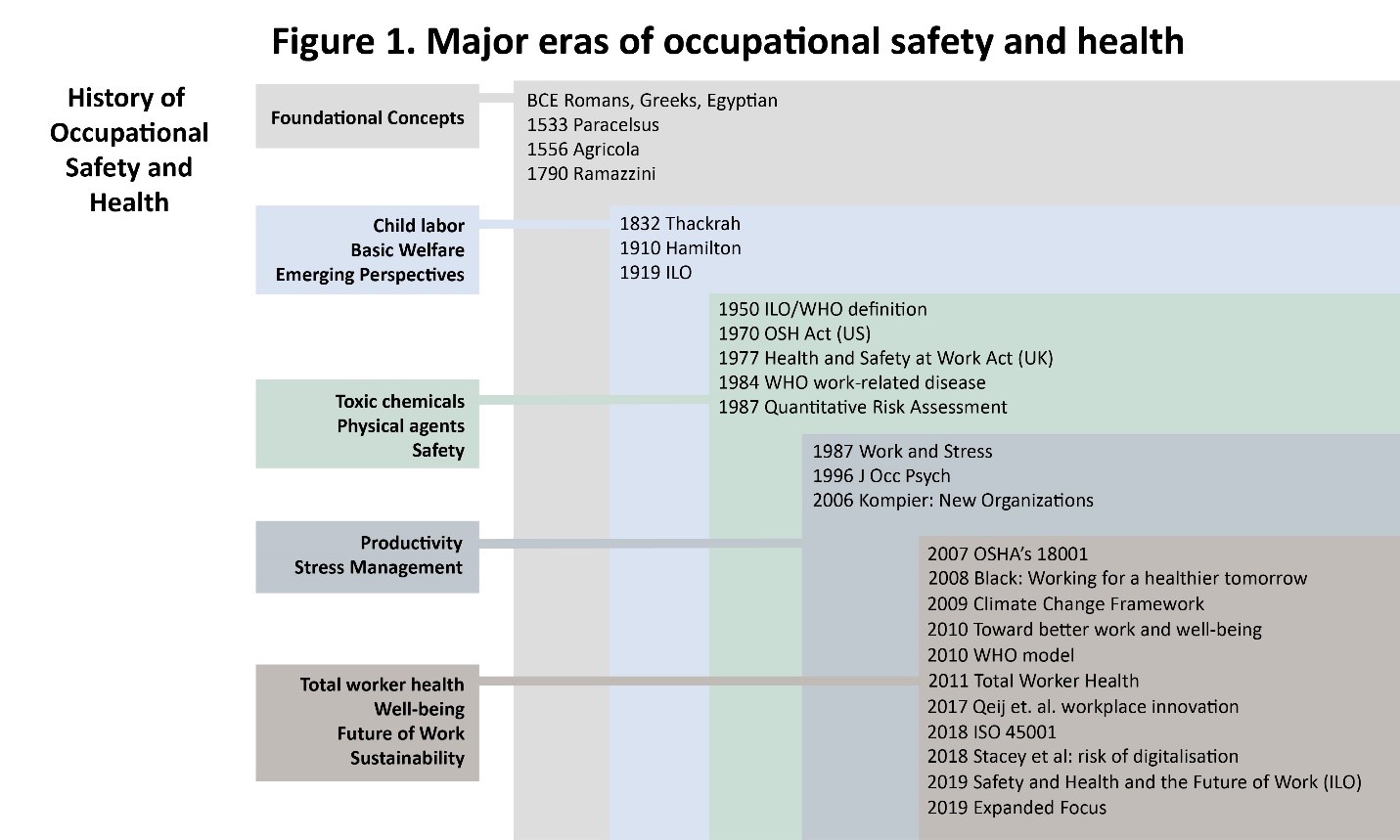

The conjunctive phrase “…and well-being” is often used in the occupational safety and health (OSH) literature in the context of health and well-being. However, historically, well-being has not been defined, operationalized, prioritized or specifically considered. To gain perspective on the concept of well-being, it is useful to think of the history of OSH in a conceptual way in terms of five overlapping characteristic eras (see Figure 1)*. These include: Foundational concepts; Child labor/basic welfare/emerging perspectives; Toxic chemicals/physical agents/safety; Health and productivity/work organization factors and stress-related disorders; and, Total Worker Health®/well-being/future of work/sustainability. The most recent era starting with the early 2000’s is influenced by:

1) the realization that the nature of work, the workforce, and the workplace is changing in major ways and at a rapid pace;

2) recognition that a large number of factors external to work such as health behaviors (e.g., alcohol and drug use), aging, pandemics, and chronic disease are influencing work and workers’ health, that some of these conditions are in turn influenced by workplace exposures, and that these factors and effects require new, systems-oriented prevention strategies;

3) growing attention to fatigue, psychosocial hazards and effects; and

4) increasing consideration of decent † , sustainable and healthy work as societal goals. [2] [3]

To better address these four contemporary factors there is need for an overarching concept such as “well-being”, that encompasses the broad range of domains in the most recent eras of OSH. In general, well-being is understood as a summative concept that characterizes the overall quality of workers’ lives (work and nonwork), including OSH aspects, and it may be a major determinant of productivity at the individual, enterprise and societal levels.[4] [5] As treated in the literature of various disciplines, well-being can be subjective, objective or a composite of the two.[6] Subjective well-being can include flourishing, happiness, satisfaction, and a sense of purpose. Objectively, well-being is having adequate food, clothing, shelter, economic resources, and legal rights.

The threat to well-being of workers is not due just to changes in work and workplace hazards, it is also due to the interaction of work and nonwork factors.[7] Such factors as demographics, economic considerations and globalization, migration, climate change and chronic disease are drivers of current and future working conditions. To optimize well-being, there is need for a comprehensive perspective that allows full consideration of possible leverage points (direction, magnitude and causality) for producing meaningful change.[8] To achieve this, we need to understand the relationship between ‘well-being in work’ and ‘well-being in life’ in terms of directionality, magnitude and causality.

Much of the literature on the relationship between ‘well-being in work’ and ‘well-being in life’ looks at the intersection between life satisfaction and job satisfaction.[9] [10] [11] Commonly it has involved cross-sectional studies where causal inference is generally not able to be assessed. More recently, a 2020 longitudinal study determined relationships between factors involved in job satisfaction and life satisfaction.[8] These relationships can be bi-directional or uni-directional (life-to-work or work-to-life).

The concept of well-being can be used in OSH in a variety of ways. As shown in Figure 2, it, can be used in research, practice, and policy. To these ends, well-being can be investigated in terms of what can cause it and its impact on productivity, organizational effectiveness, and health-related outcomes. Well-being may prove to be a leading indicator of these outcomes. It can be a practical objective for employers and workers, and it can be the target of policy or an indicator of whether a policy achieves well-being.

If the concept of well-being is to be operationalized for use as an objective or a condition of workers or organizations there is a need for a way to measure it. The literature on measuring well-being is broad and provides many approaches.[12] The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) developed a conceptual framework for worker well-being that includes five domains and 20 subdomains that have been incorporated in a survey instrument called the NIOSH WellBQ.[13] [14] The instrument may be useful as a tool for research, practice and policy development.

Ultimately, if the concept of well-being is to be used by OSH in the future there is need for the OSH field to be prepared for, and to have the capacity to use it. This preparation requires that, in the future, OSH investigators and practitioners need to have appropriate training, understanding of relevant complementary disciplines, and the readiness to think about OSH concerns from a multifactorial perspective. Three approaches to expand OSH training to address well-being can be envisioned. One pertains to increasing the knowledge base and skill sets of OSH practitioners and investigators with augmented training and systems-thinking that is inclusive of extra-organizational influences and cross-disciplinary perspectives and approaches. The second is to engage professions outside the OSH discipline to understand basic principles of OSH, expand their attention toward OSH and to develop collaborations and partnerships with OSH professionals. The third would be a combination of both.[15] For all three approaches to focus on well-being as an outcome of OSH activity, a holistic analysis of worker health and well-being is needed.

The OSH field will need to have a more transdisciplinary focus. A transdisciplinary focus means that researchers and practitioners from different disciplines work jointly using a shared conceptual framework drawing together disciplinary-specific theories, concepts and approaches to address common problems.[15] Recognizing the need for a more holistic framework in OSH, NIOSH has initiated a new program of research under the rubric of Total Worker Health ® (TWH) to better understand how conditions inside and beyond the work environment combine to influence the well-being of workers, to develop integrative prevention strategies that cross these domains to improve worker well-being, and to improve the capacity of occupational health professionals in systems approaches to OSH.[16]

While OSH professionals generally take a systematic approach to their work, how to train OSH professionals in systems-thinking and skills could be a challenge because of the multifactorial nature of so many of the contemporary and emergent OSH problems, [15] although training programs of this nature have already been initiated by some partners of the NIOSH TWH program. Systems thinking in OSH involves taking a holistic view of factors and interactions that contribute to problems, diseases, and outcomes in workers. [17]

Ideally, OSH will become part of a societal consideration that includes sustainability, climate change, decent work and a future impacted heavily by technology, all impacting work and worker well-being and requiring more expansive intervention strategies in OSH. As noted, in this scenario, researchers and practitioners conducting research and developing and implementing OSH interventions will require a broader set of skills and perspectives.[18] Psychosocial hazards in particular will likely become an even greater problem for workers and employers, necessitating additional skills and new inter-disciplinary partnerships for OSH professionals., While recognizing the increasing role of psychosocial hazards and adverse effects, the OSH field will also have to address the ongoing threats of all hazards which the current era overlaps with as shown in Figure 1, as well as new physical, chemical, and biological hazards.

Ultimately, adoption of the well-being concept in OSH will require further agreement on how to operationalize the concept and development of investigatory and intervention strategies that reach beyond the workplace. It is important to guard against blaming the workers for poor well-being outcomes and to consider privacy and confidentiality concerns when addressing non-work characteristics. Additionally, because some interventions necessary to address the well-being of workers may be outside the control of the workplace, broader society-level policies, changes in personal choice-making, clinical services, and health promotion interventions will be necessary to affect well-being in these instances.

Critical in the evolution of OSH (from a labor to more of a public health perspective) will be the need to address not only hazards in work and elsewhere as they relate to worker well-being, but also lack of workers’ opportunity in terms of unemployment and underemployment. The technological displacement of workers is a growing issue and one that will affect the workforce into the future. The impact of underemployment and unemployment on well-being has been richly described; however, in the future it may become more significant. Intervention to address this will be a challenge for OSH. The field will have to evolve to address lack of employment opportunity as a hazard to workers by adopting a more public health approach to worker health. Additionally, the OSH field may have to think not only of hazards to workers, but hazards to, and characteristics of the workforce, and the health and welfare of workers’ families (Figure 3) ‡ . Strategies to affect all or parts of the workforce will be of critical importance. Both of these new focal areas for OSH are well beyond historical practices and perspectives. However, they ultimately tie to worker well-being and a more broadly prepared field of OSH professionals would ideally be well-positioned to pivot, evolve, and envision solutions and quickly implement them.

Paul A. Schulte, Ph.D., is the Director of the NIOSH Division of Science Integration.

Steven L. Sauter, Ph.D., is a consultant to the NIOSH Total Worker Health program.

The authors thank David DeJoy, Kent Anger, Casey Chosewood, Anita Schill, Chia-Chia Chang for review comments and Vanessa Williams and Nicole Romero for assistance on the figures and Jo Ann Norton for processing.

This blog is part of a series for the NIOSH 50th Anniversary. Stay up to date on how we’re celebrating NIOSH’s 50 th Anniversary on our website.

* These eras represent the authors’ interpretation of occupational safety and health history based on supporting literature. See Melling and Carter (2012) [19] for further discussion.

† “Decent work sums up the aspirations of people in their working lives. It involves opportunities for work that is productive and delivers fair income, security in the workplace and social protection for families, better prospects for personal development and social integration, freedom for people to express their concerns, ability to organize and participate in decisions that affect their lives, and equality of opportunity and treatment for all women and men.” ILO [20]

‡See the 2012 WHO report on the importance of health, safety, and well-being at work.[21]

1. Black C. [2008]. Working for a healthier tomorrow. London England: The Stationary Office.

2. Burton J [2010]. Healthy workplaces: a model of action for employers, workers, policy-makers and practitioners. Geneva Switzerland: World Health Organizations.

3. Howard J. Nonstandard work arrangements and worker heath and safety. Am J Ind Med 60 (1): 1-10, 2017.

4. Schulte PA, Vainio H [2010]. Well-being at work – overview and perspective. Scan J Work Environ Health 36(5):422-429.

5. Gervais R, Buffet M-A, Liddle M, Eekelaert L [2019]. Well-being at work: creating a positive work environment. European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

6. Schulte, PA, Guerin RJ, Scholl AL, Bhattacharya A, Cunningham TA, Pandalai S, Eggerth D, Stephenson CM. [2015]. Considerations for incorporating “well-being” in public policy for workers and workplaces. AJPH, August 0015; 106 (f) 31_e44, https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/full/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302616#.

7. Schulte PA, Pandalai S, Wulsin V, Chun K. Interaction of occupational and personal risk factors in workforce health and safety. Am J Public Health 102; 434-448, 2012. Pls let me know if you have further questions.

8. Weziak-Bialowolski D, Bialowolski P, Luigi Sacco, VanderWeele TJ, McNeely E [2020]. Well-being in life and well-being at work: which comes first? Evidence from a longitudinal study. Front. Public Health. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00103/full

9. Bowling NA, Eschleman KJ, Wang Q [2010]. A meta-analytic examination of the relationship between job satisfaction and subjective well-being. J Occup Organ Psychol. 83:915–34. doi: 10.1348/096317909X478557.

10. Judge TA, Watanabe S [1993]. Another look at the job satisfaction-life satisfaction relationship. J Appl Psychol 78:939-948. Doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.78.6.939.

11. Rain JS, Lane IM, Steiner DD [1991]. A current look at the job satisfaction/life satisfaction relationship: review and future considerations. Human Relations. (1991) 44:287–307. doi: 10.1177/001872679104400305.

12. Cooke PJ, Melchart TP, Connor K [2016]. Measuring well-being: a review of instruments. The counseling psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016633507.

13. Chari R, Chang C-C, Sauter SL, Petrun Sayers EL, Cerully JL, Schulte PA, Scholl AL, Uscher-Pines L [2018]. Expanding the paradigm of occupational safety and health: a new framework for worker well-being. JOEM 60:921-929.

14. NIOSH [2021]. NIOSH worker well-being questionnaire (WellBQ). By Chari R, Chang CC, Sauter SL, Petrun Sayers EL, Huang W, Fisher GG. Cincinnati, OH: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2021-110 (revised 5/2021), https://doi.org/10.26616/NIOSHPUB2021110revised52021

15. Schulte PA, Delclos G, Felknor SA, Chosewood LC [2019]. Toward an expanded focus for occupational safety and health. Int J Environ Res and Public Health 16, 4946; DOI:10.3901/jerph 16244946.

16. Hudson HL, Nigam JAS, Sauter SL, Chosewood LC, Schill AL, Howard J [2019]. Total Worker Health. American Psychological Association Washington D.C. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000149-000

17. Carey G, Malbon E, Carey N, Joyce A, Crammond B, Carey A [2015]. Systems science and systems thinking for public health: a systematic review of the field. BMJ open. 5(12):e009002. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009002.

18. Schulte PA, Streit JMK, Sheriff F, Delclos G, Felknor SA, Tamers SL, Fendinger S, Grosch J, Sala R [2020]. Potential scenarios and hazards in the work of the future: A systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature and gray literatures. Ann Work Exp and Health 1-31. Doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxaa051.

19. Melling J, Carter T [2012]. Donald Hunter and history of occupational health: precedents and perspectives. In Baxter ed al (eds) Hunter’s diseases of occupations. Pp5-23. https://doi.org/10.1201/b13467

20. International Labour Organization. Decent Work. https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/decent-work/lang–en/index.htm

21. Kim, P. [2012]. WHO and well-being at work. Presentation well-being at work 2012. Manchester UK May 21, 2012. https://www.hsl.gov.uk/media/202146/5_kim_who.pdf

Posted on June 7, 2021 by Paul A. Schulte, Ph.D., and Steve L. Sauter, Ph.D. Categories 50th Anniversary Blog Series, Total Worker Health, Well-beingComments listed below are posted by individuals not associated with CDC, unless otherwise stated. These comments do not represent the official views of CDC, and CDC does not guarantee that any information posted by individuals on this site is correct, and disclaims any liability for any loss or damage resulting from reliance on any such information. Read more about our comment policy ».